A gorilla walking directly in front of your field of vision and waving its hand at you is the kind of thing you’d think wouldn’t be hard to notice. But last year, when I spoke with Daniel Simmons, I learned that if the brain is distracted enough, that gorilla would be completely invisible to you.

A gorilla walking directly in front of your field of vision and waving its hand at you is the kind of thing you’d think wouldn’t be hard to notice. But last year, when I spoke with Daniel Simmons, I learned that if the brain is distracted enough, that gorilla would be completely invisible to you.

What I spoke with Daniel Simmons about was his book, The Invisible Gorilla: How Our Intuitions Deceive Us, and the fascinating subject of change blindness, our inability to spot seemingly obvious changes in our surroundings. The subject was so interesting to me that I thought I’d revisit it today.

Things got pretty strange.

1. Why you can’t remember if your friend wears glasses

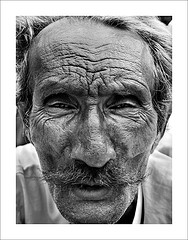

Ever see somebody and just know something’s different, but have absolutely no idea what? It turns out this is related to the subject of change blindness, as well as the fact that our brains are hard wired to recognize faces.

Ever see somebody and just know something’s different, but have absolutely no idea what? It turns out this is related to the subject of change blindness, as well as the fact that our brains are hard wired to recognize faces.

As humans, we care a lot more about human faces than just about anything else. That’s why our brains are hard wired to process faces more “holistically,” meaning that we visually process the whole face, not just the individual parts of it.

It turns out, as a side effect, this makes it easier for us to spot changes in faces, but harder to pinpoint exactly what the change is. This is a very specific, and bizarre, form of change blindness.

Participants at Iowa State University were asked to look at sequences of images, including not just faces, but ordinary objects, like houses.

When they looked at faces, if the experimenters swapped out a chin, eye, nose, or some other part of the face, the participants were very good at noticing that something had changed, in comparison with, say, a house.

On the other hand, when they were asked to specify exactly what had changed, they were far more likely to point out that, say, a chimney had been replaced, than that a chin had.

2. An entire scene can change color without you noticing a thing

One of the more interesting change blindness experiments I came across demonstrated, for the first time, that it’s easier to spot changes in objects than changes in color, oddly enough.

One of the more interesting change blindness experiments I came across demonstrated, for the first time, that it’s easier to spot changes in objects than changes in color, oddly enough.

The volunteers were asked to look at a series of pictures, and to point out what was different. In each case, an object had disappeared, an object had been added, or the scene had changed color.

In previous studies, the images were put together by human experimenters, who decided where to make the changes and what kinds of changes to make. But in this one, the bias was eliminated by introducing a computer algorithm.

The main goal of the experiment was to eliminate any bias from “saliency.” Saliency is the tendency for something to jump out at us. The concern was that when humans designed the experiment, the saliency was biased, so it was difficult to figure out just what kinds of changes we’re blind to the most.

The study confirmed that the computer was capable of making predictions about when we are most likely to notice a change, and to control for the impact of saliency.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the most noticeable change wasn’t a change in the color of the scenery. It was the addition or removal of an object.

This shocked the scientists, since color is such an important part of the way we perceive things. It was only possible to detect this effect by controlling for saliency.

The study was led by Milan Verma at Queen Mary, University of London. The researchers expect this knowledge to be used in the design of road signs and visual information, so that viewers won’t accidentally skim right over important information.

3. Magicians hack our short term memory to create change blindness

Before this particular experiment, scientists debated the source of change blindness in the brain. Did we simply ignore certain pieces of an image, never even recording it to our visual short term memory? Or did we just have trouble comparing consecutive images in the brain?

Before this particular experiment, scientists debated the source of change blindness in the brain. Did we simply ignore certain pieces of an image, never even recording it to our visual short term memory? Or did we just have trouble comparing consecutive images in the brain?

In this experiment, the scientists took advantage of a century old magic card trick.

The study, which was led by Dr. Luis M. Martinez at the Instituto de Neurosciencias de Alicante in Spain, found that we have no trouble committing images to short term memory. Even objects that we aren’t focusing on are passively placed in our brain’s visual “RAM,” so to speak.

This means that change blindness isn’t the result of a failure to see things that we aren’t focused on. Instead, it’s an inability to consciously compare two scenes.

The study also discovered that our visual short term memory is extremely volatile and easily erased. That’s why magicians can so easily hack our visual cortex with a few words and a bit of misdirection.

Martinez was careful to explain to the Society for Neuroscience that change blindness is typically a “good thing.” It prevents us from getting distracted.

It does have a dark side, however, when it means that patients get “the wrong medications at busy hospitals, say, or traffic accidents [are] caused by overtaxed cab drivers.”

4. Our intentions determine what we see and what we don’t

Another one of the change blindness examples I came across demonstrates how we subconsciously “choose” what we see and what we don’t. It’s all about the way we plan to interact with our environment.

Another one of the change blindness examples I came across demonstrates how we subconsciously “choose” what we see and what we don’t. It’s all about the way we plan to interact with our environment.

In this experiment, held at Plymouth University, the participants were asked to look at images of fruit. When they spotted a change in the image, they were asked to grab a device.

What the researchers discovered was that the size of the device impacted how quickly the change was spotted. For example, if the device was small, they were more likely to spot a change in a strawberry. If the device was large, they were more likely to spot a change in a banana.

In other words, the intent to grab something of a specific size caused them to pay more attention to things that were about the same size.

This suggests that change blindness is the result of an interaction between us and our environment. On some level, we have control over what we see, and what we don’t.

5. “Auditory” Change Blindness Works Differently

Apparently, our auditory short term memory is more efficient than our visual short term memory, at least when it comes to comparing sequences and listening for change.

Apparently, our auditory short term memory is more efficient than our visual short term memory, at least when it comes to comparing sequences and listening for change.

One circumstance where change blindness becomes especially prominent is when there is a visual gap. If we’re watching a continuous scene, a sudden change in the image is more jarring and more likely to attract our attention, provided something else doesn’t distract us.

But if the scene blacks out for even a tenth of a second, we notice only the most obvious changes.

Researchers at the Association for Psychological Science wanted to find out if the same thing happened with sounds.

The participants listened to chords consisting of a complex combination of tones. The more complicated the chords were, the harder it was for them to detect a change. So, in some sense, this could be called change blindness.

However, the gap between hearing the sounds had no impact.

Whether the sound was replaced immediately, or there was a gap in between the changes, they did equally well at detecting changes.

In other words, we simply don’t listen for change the same way that we look for it. The mechanism behind it seems to be very different. Our auditory memory doesn’t get wiped clean as often as our visual memory does.

Change blindness is, to me, evidence of the selective reality we live in. We tend to see only what we anticipate, what we think has the most impact on us, and what we have control over. It weeds out distractions, but can it also close us off?

Want to let others know about change blindness? Pass this along if you find it as interesting as I do, and check out this book if you’d like to learn more:

The Invisible Gorilla: How Our Intuitions Deceive Us

What Does Memory Have to Do With Intelligence?