As we dig deeper into the structure of DNA, we learn more about the code that serve’s as life’s encyclopedia. In The Violinist’s Thumb, Sam Kean explores what DNA is, how it influenced historical figures, and what it can tell us about what it means to be human.

I recently had the opportunity to ask him a few questions on the subject. Here’s what he had to say.

The Interview

It’s good to have you here, Sam.

Glad to be here.

So first off, you make a living using offbeat anecdotes about science in public speeches and books. How did you end up falling into a profession like that?

Temperament. Those are just the stories I gravitate toward—funny, spooky, oddball incidents from our past. And while I love science generally, and even got a college degree in it, I just didn’t have the temperament to practice science day-to-day.

Temperament. Those are just the stories I gravitate toward—funny, spooky, oddball incidents from our past. And while I love science generally, and even got a college degree in it, I just didn’t have the temperament to practice science day-to-day.

In science labs, instruments are always breaking, or you’re constantly writing grant applications, and it’s incredibly frustrating work. Writing was more palatable to me, since words do what you tell them to. And in writing about offbeat science history, I could keep up with science without having to specialize in any one field.

Alright, a bit about your book. Genetics and history are about as different as two subjects can get. What are some of the unexpected ways the two meet?

I wrote the book because there are so many incidents in human history that we once thought lost forever—they just happened so long ago. But because we can now read our DNA, we have uncovered these lost details for the very first time.

One of my favorite chapters in the book was about a topic I call retrodiagnoses. The basic idea is to figure out how your favorite historical celebrity died, and I look at Lincoln, Darwin, the violinist Niccolò Paganini, and others.

One of my favorite chapters in the book was about a topic I call retrodiagnoses. The basic idea is to figure out how your favorite historical celebrity died, and I look at Lincoln, Darwin, the violinist Niccolò Paganini, and others.

What I love about this field is that you can start with something like DNA work, and parlay that information into all sorts of other information about the era’s history and culture. The DNA tests on King Tut are probably the best example of that.

Just as important, DNA can reveal a lot about our deep human history—the history of how our species first arose and first spread across the globe, long before we had written records or even permanent dwellings. That entire grand saga is etched into our DNA. And believe it or not, we can get details about our past from non-human DNA as well.

A few years ago scientists compared the DNA of head lice (which have lived on human scalps since forever) and body lice (which are related to head lice, but can only live in clothes) to determine when the two forms of lice split into different species. Because body lice can only live in clothes, that date is a good guess about we first started wearing animal skins to cover ourselves up.

A few years ago scientists compared the DNA of head lice (which have lived on human scalps since forever) and body lice (which are related to head lice, but can only live in clothes) to determine when the two forms of lice split into different species. Because body lice can only live in clothes, that date is a good guess about we first started wearing animal skins to cover ourselves up.

I could go on, but overall I think genetics will rewrite a lot of what we “knew” about human history.

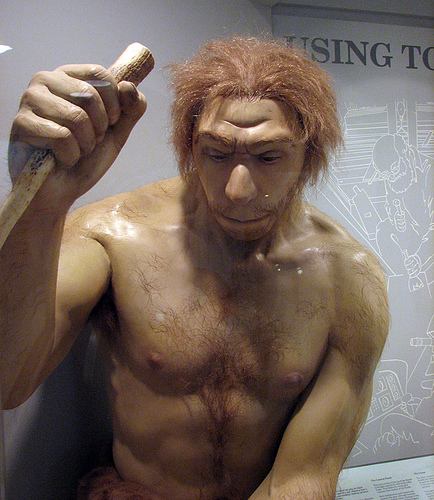

I was also wondering what your thoughts were on the possibility that Africans interbred with an unknown species, and the less controversial evidence that Europeans interbred with neanderthals.

It’s something I discuss in the book, and it’s a good example of how history can be rewritten with DNA. We already have solid evidence of two extra-species liaisons between us and other hominids (with Neanderthals, and with Denisovins, a recently discovered species). Heck, most people still have, even today, something like 3 percent Neanderthal DNA inside them! And given that we and other hominids originated in Africa, the odds are good that we’ll find evidence for similar affairs there.

It’s something I discuss in the book, and it’s a good example of how history can be rewritten with DNA. We already have solid evidence of two extra-species liaisons between us and other hominids (with Neanderthals, and with Denisovins, a recently discovered species). Heck, most people still have, even today, something like 3 percent Neanderthal DNA inside them! And given that we and other hominids originated in Africa, the odds are good that we’ll find evidence for similar affairs there.

Some people find the whole thing icky, which I understand. But I really think it expands our sense of who we human beings are and how we fit in with other life on earth. And it’s a great example of how genetics has spilled out of its original boundaries of just medicine. It has become one of the most powerful tools in archaeology already, and there’s still more out there to learn.

We’ve learned that DNA is far more complex and fascinating than we would have thought, and that evolution doesn’t quite work the way we’re usually taught. What are some of the most interesting facts here that most people are completely ignorant of?

I can think of two. You have about six linear feet of DNA in every cell inside you. And yet that DNA has to cram into a nucleus that’s only about one one-thousandth (1/1000th) of an inch wide. That’s so much compression, in fact, that “cram” doesn’t even begin to cover it. As far as the total amount of DNA in your body, if you strung it all end to end, bit by bit, it would stretch roughly from the Sun to Pluto and back.

I can think of two. You have about six linear feet of DNA in every cell inside you. And yet that DNA has to cram into a nucleus that’s only about one one-thousandth (1/1000th) of an inch wide. That’s so much compression, in fact, that “cram” doesn’t even begin to cover it. As far as the total amount of DNA in your body, if you strung it all end to end, bit by bit, it would stretch roughly from the Sun to Pluto and back.

The second fact—something that still blows my mind any time I think of it—is how much DNA in our body isn’t really “ours.” Old, broken-down virus DNA actually makes up 8 percent of the human genome. The DNA that we traditionally think about as genes—that is, DNA that eventually leads to proteins—makes up less than 2 percent of our DNA. So by that measure at least, we’re four times more virus than human!

Most of that virus DNA doesn’t do anything; again, it broke down long ago. But some of it does still function. In fact one of the key genes for making the placenta—the interface between a mother and her fetus—was almost certainly stolen from a virus long ago.

I could probably talk about this with you forever, so let’s finish this up by asking what the implications of all this are?

Genetics will obviously be an important part of medicine in the future. But in parallel with that, DNA has already revealed an incredible amount to us about our past—stories from our very earliest hours as a species all the way up to the glories of modern civilization.

And in fact, beyond the ways we usually think about genetics benefiting humankind—instant diagnoses, medical panaceas, things for our physical bodies—I think that some of the most profound changes that genetics brings about will be mental enrichment and even a sort of spiritual enrichment.

I think genetics can give us a more expansive sense of who humans are, where we came from, how we fit with other life on earth, and what makes us both one of nature’s most absurd creatures, and its crowning glory.

Take a look at Sam’s book: The Violinist’s Thumb: And Other Lost Tales of Love, War, and Genius, as Written by Our Genetic Code

Sleep and Memory: The Sleeping Brain Acts Like it’s Remembering