Across the political spectrum, almost everybody agrees that the school system is broken. Unfortunately, most of the blame gets passed onto the people who have the least ability to fix the problem: teachers. There may be a few bad apples, but by and large teachers are very bright individuals who are extremely knowledgeable about the subjects they teach. Why, then, does the school system have so many problems?

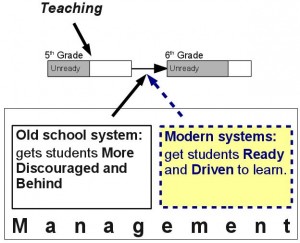

Robert Caveney believes that the problem is systemic. In his book, SCHOOLING for Readiness and Drive, he argues that the problems can be solved using methods that have already been used by other systems. The problem is that the school system has failed to realize what education really is: a form of knowledge work.

Kids want to learn, but the system only succeeds in discouraging most of them.

The Interview

It’s a pleasure to speak with you, Robert.

Thank you Carter, for this opportunity.

So you’re the author of SCHOOLING for Readiness and Drive, which offers several suggestions for fixing the school system. If I understand you correctly, it’s your opinion that the school system uses a very outdated method, and that it should embrace more modern management strategies. Before we get into that, I’d like to hear what you think the school system is actually for.

The school system must have two aims: first, to year over year, get students ready for next year’s learning and secondly, release the natural drive to create and learn. I am agnostic about the various philosophies of what it means to become educated. Those decisions are made in a conversation over generations. Once it has been decided what students should learn, a system is required to assure that our children achieve these desired results.

The school system must have two aims: first, to year over year, get students ready for next year’s learning and secondly, release the natural drive to create and learn. I am agnostic about the various philosophies of what it means to become educated. Those decisions are made in a conversation over generations. Once it has been decided what students should learn, a system is required to assure that our children achieve these desired results.

The first priority, readiness to learn, is the highest priority because unready problems compound year over year when students aren’t ready. Giving an 8th grade algebra teacher students who aren’t ready dramatically increases the challenge of teaching and learning. It only gets worse, year over year, if we don’t assure readiness to learn.

The second priority, to release the natural Drive to learn, comes from some common sense and some science. It turns out students are the only people who can do the learning work. Science tells us that extrinsic motivation, rewards and punishment, while effective for production work, slows knowledge workers down. There is a wonderful book by Daniel H. Pink titled DRIVE: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, which shows the indisputable science that intrinsic motivation is what is required to accomplish learning.

These are not “nice-to-have” features of a system of schooling, these are “must-have” features of a school system.

These are not “nice-to-have” features of a system of schooling, these are “must-have” features of a school system.

If only intrinsic motivation is effective for learning (knowledge work), then clearly the school system must have a system for releasing the natural drive to learn. For all of these reasons, the two must-have features of a school system are processes to assure readiness and methods to release natural drive. These are not “nice-to-have” features of a system of schooling, these are “must-have” features of a school system.

I am so glad that you mentioned this aspect of motivation, which is something that I actually alluded to in the very first post on this site. The assumption that carrots and sticks can solve everything has been discredited using almost every method available to modern science, but it continues to be used in the wrong context by almost every socioeconomic system. One good example is the insistence that merit pay would improve the educational system.

Ah, merit pay. So glad you brought that up. It is amazing how well this has been proven to not work – for three hundred years. Following is text right from my book about the history of merit pay. It’s not pretty.

A HISTORY OF MERIT PAY

A HISTORY OF MERIT PAY

AROUND 1710, TEACHERS SALARIES TIED TO CHILDREN’S SCORES FAILS TO IMPROVE SCORES

I am not making this up. It didn’t work. But that hasn’t prevented several more efforts over the last 300 years.i

1890 ENGLAND, AFTER 30 YEARS, TEACHER MERIT-PAY REJECTED

“In 1890, after 30 years, the “overwhelming judgment” in the country was that the practice was “unsound policy,” and it was dropped. By 1904, reflecting a strong negative reaction to previous practice, the education code for the country embodied a substantially different approach to the education of children. The job of teachers was described as “assisting” children to learn, and the ministry handbook in 1905 called for “unlimited autonomy” for teachers.”ii

1986 HARVARD EDUCATIONAL REVIEW, V56 N1 P1-17 FEB 1986

The authors of this article use micro-economics to show that teaching is not an activity for which performance pay is useful.iii

2005 PAY-FOR-PERFORMANCE IN DENVER

“Denver’s Pay for Performance pilot was the most ambitious experiment in teacher compensation ever attempted. The verdict: test-based pay for performance doesn’t work.”, says Donald G. Gratz, who led the research team for the first half of the pilot.iv

NOVEMBER 4, 2009 TEXAS MERIT-PAY PILOT FAILED TO BOOST STUDENT

SCORES, STUDY SAYS

In the new study…we learn whether the pay incentives for teachers translated to any improvements in their students’ test scores. The answer, in a word, is no.

In the new study…we learn whether the pay incentives for teachers translated to any improvements in their students’ test scores. The answer, in a word, is no.

“Piloted between the 2005-06 and the 2008-09 school years, the now-defunct Governor’s Educator Excellence Grants, or GEEG, program distributed more than $10 million a year in federal grants to 99 Texas schools…In the new study, released just this month by the same group of researchers, we learn whether the pay incentives for teachers translated to any improvements in their students’ test scores. The answer, in a word, is no.”v

CHICAGO 1995 – 2010

1995 BOLD NEW SYSTEMIC IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY – WITH TEACHER

COMPENSATION – MILKEN FOUNDATION – TAP

“The Milken Family Foundation has proposed a bold new, systemic school improvement strategy. Its goal is to improve the quality of the teaching profession because excellent teachers enhance student learning. This program, known as the Teacher Advancement Program, or TAP, has five components, one of which is performance-based compensation. Salaries depend upon teacher achievements, teacher performance, tasks undertaken, and student achievement. Thus it is important to understand the pros and cons of performance-based compensation.

The purpose of this paper is to compile and analyze the current and historical criticisms of performance-based compensation in K-12 education. We believe that new compensation methods are not only feasible, but necessary, in order to attract the best and the brightest into the teaching profession, keep the most effective of these in teaching, and motivate all teachers.”vi

2006 27.5 MILLION TO PILOT MERIT PAY INITIATIVE BASED BASED ON MILKEN FOUNDATION TAP PROGRAM

“Chicago Public Schools snared its biggest federal grant to date when it won $27.5 million to pilot a merit pay initiative for teachers, making Chicago the largest district in the country to

experiment with performance-based pay.

The pilot will be modeled on the highly regarded Teacher Advancement Program, developed by the Milken Family Foundation and overseen by the National Institute for Excellence in Teaching.”vii

JUNE 1, 2010 CHICAGO MERIT-PAY MODEL FAILS

Preliminary results from a Chicago program…show no evidence that it has boosted student achievement on math and reading tests…

Preliminary results from a Chicago program…show no evidence that it has boosted student achievement on math and reading tests…

“Preliminary results from a Chicago program containing performance-based compensation for teachers show no evidence that it has boosted student achievement on math and reading tests, compared with a group of similar, nonparticipating schools, an analysis released today concludes.

The study also found that the Chicago Teacher Advancement Program, a local version of the national TAP program, did not improve the rates of teacher retention in participating schools or in the district

The findings cover the first two years of the program’s four-year implementation in select schools…”viii

2010 VANDERBILT STUDY

“Rewarding teachers with bonus pay, in the absence of any other support programs, does not raise student test scores, according to a new study issued today by the National Center on Performance Incentives at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of education and human development in partnership with the RAND Corporation.

This and other findings from a three-year experiment – the first scientific study of performance pay ever conducted in the United States – were released at a conference on evaluating and rewarding educator effectiveness hosted by the National Center on Performance Incentives at Vanderbilt.” MELANIE MORAN, VU NEWS, NASHVILLE, Tenn.- September 21, 2010

What do they say, if you get the same results over and over again for 300 years expecting different results?

What do they say, if you get the same results over and over again for 300 years expecting different results?

The proponents of merit-pay are largely business proponents living in the old paradigm of Motivation 2.0, who foist these initiatives on the school system, over and over and over gain.

What do they say, if you get the same results over and over again for 300 years expecting different results? That’s just crazy, right?

This is a pretty solid history. It’s tempting to believe that you can motivate somebody to do a better job with money, but it just doesn’t work that way when it comes to knowledge work.

Now almost everybody seems to agree that something is wrong, but before we even get into that I’d like to have some idea of what the logic behind the current system is. What ideologies is it based on, and how are they being implemented?

In the early 1900s, agriculture, mining and manufacturing showed spectacular improvements in productivity because of the use of a new method of management, The Taylor System, also known as Scientific Management, invented about 1890 by Frederick Winslow Taylor. Muckraking journalists exercised the public with the new sin of that age: waste and inefficiency, causing a huge amount of public pressure. Beginning in 1913, education managers began adopting and adapting, what had been so clearly proven to be a superior method of management. What nobody knew, or could prove at the time, was that this new method, Scientific Management, did not work for knowledge work. In fact the phrase “knowledge work” wouldn’t even be coineduntil 1959 by the great management consultant, Peter Drucker.

In the early 1900s, agriculture, mining and manufacturing showed spectacular improvements in productivity because of the use of a new method of management, The Taylor System, also known as Scientific Management, invented about 1890 by Frederick Winslow Taylor. Muckraking journalists exercised the public with the new sin of that age: waste and inefficiency, causing a huge amount of public pressure. Beginning in 1913, education managers began adopting and adapting, what had been so clearly proven to be a superior method of management. What nobody knew, or could prove at the time, was that this new method, Scientific Management, did not work for knowledge work. In fact the phrase “knowledge work” wouldn’t even be coineduntil 1959 by the great management consultant, Peter Drucker.

What is this 1890′s Scientific Management? It has two pillars. The first is a system for organizing the work of many, which has five elements. The second pillar is a system for eliciting the best contribution from each person, for which purpose extrinsic motivation was chosen, rewards and punishments. The five elements of the organizing part are (1) Time & Motion Studies, (2)The Task Idea, (3) Standardization, (4) Functional Foremanship (my favorite) and finally, (5) Central Planning.

…teachers get a teaching schedule from central planners…and…don’t report to central planners, but instead to principals who have nothing to do with the schedule.

…teachers get a teaching schedule from central planners…and…don’t report to central planners, but instead to principals who have nothing to do with the schedule.

We all recognize how teachers get a teaching schedule from central planners (curriculum & instruction department) and how teachers don’t report to central planners, but instead to principals who have nothing to do with the schedule. This management structure is called Functional Foremanship. Functional Foremanship was jettisoned by industry early on, in favor of something called “Unity of command”, a nice formal hierarchical organizational structure. The school system has kept Functional Foremanship, along with all five elements of 1890s Scientific Management to this day.

To see how this system works in practice, put a well-trained, dedicated teacher in a classroom with some students who are ready to learn the current material, some who are unready to learn and some who are discouraged. Those students who are ready have a chance to comply and keep up, but those who are unready or discouraged are naturally more likely to fall behind. The teacher has a schedule to keep. Repeat this year over year to get the results we get, students getting more discouraged and behind, so much so that too many drop out of school altogether believing they are failures.

I’m glad you mention autonomy, because I feel like that is a key piece of the puzzle. Can you point to examples of more autonomous systems where knowledge work is performed? What do these systems look like?

Daniel H. Pink, in DRIVE: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, reviews several examples of how autonomy is used in business to increase productivity (Google, 3M, Best Buy and others), and he also cites research showing that more autonomy measurably helps release more of students own intrinsic motivation to learn.

Daniel H. Pink, in DRIVE: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, reviews several examples of how autonomy is used in business to increase productivity (Google, 3M, Best Buy and others), and he also cites research showing that more autonomy measurably helps release more of students own intrinsic motivation to learn.

But perhaps the best way to explain what these systems look like is with a true story. One day I took my kids to a park to try the sport of orienteering, where the idea is to find goals on a map, and record how quickly they are found with a little electronic key. Starts are staggered so those ahead don’t inadvertently give clues to those behind.

The kids complained all the way across this very large park. “Why did you bring us here? This is Saturday dad! I want to be with my friends!” But once given maps and goals they ran around the park twice! (I could hardly keep up.)

Mastery is a challenge which is not too easy (boring) and not to hard (frustrating), but just right for engagement.

Mastery is a challenge which is not too easy (boring) and not to hard (frustrating), but just right for engagement.

Why? Mastery is a challenge which is not too easy (boring) and not to hard (frustrating), but just right for engagement. In addition, Mastery requires perfectly immediate feedback. “Is this the tree on the map? No. There is no box to insert the key in.” This pre-built course gave students the opportunity to develop Mastery with Autonomy. And it worked. It was like flipping a switch.

What is the system? To provide the conditions of Autonomy and Mastery, do it yourself work must be built ahead of time. The “system” is a system of do-it-yourself challenges built ahead of time (plus management methods which we haven’t discussed, to ensure student’ readiness to tackle the challenges.) The system, whatever it is, is the responsibility of management.

Thanks for that. This makes sense not only from a scientific perspective, but from a common sense one. Even somebody who has an intrinsic interest in academic subjects, like me, can remember disliking the school system. Considering that I love to learn, this is a sign that something is seriously wrong.

Now we all seem to agree on that point. Do you think that has more to do with the implementation or the fundamental approach? Why isn’t the system accomplishing what we expect it to?

As David Hannah famously said, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results that it gets.”

We can expect the system we are using to continue to get the results it gets, because as a practical matter, it is perfectly designed to get the poor results it gets.

We can expect the system we are using to continue to get the results it gets, because as a practical matter, it is perfectly designed to get the poor results it gets.

We can expect the system we are using to continue to get the results it gets, because as a practical matter, it is perfectly designed to get the poor results it gets.

At this point it might be worth pointing out that I don’t know anything about teaching, and precious little about learning.

The problems we have are not teaching problems, by and large, they are system problems. To paraphrase another famous quote: It’s the system stupid.

Well said. I recall hearing about a study that discovered the amount of education a teacher had didn’t have much to do with how effective they were as a teacher. This puts us in a catch 22 situation. If picking the cream of the crop from the educational system doesn’t provide you with the best teachers, how important can a good teacher really be?

We might as well shorten the instructions to: “Do the impossible.”

We might as well shorten the instructions to: “Do the impossible.”

Teachers are put in an impossible situation, given 150 students and told to “follow the schedule” and “use differentiated instruction”. We might as well shorten the instructions to: “Do the impossible.”

It’s the system stupid, perfectly designed to get students more discouraged and behind.

Absolutely.

Unfortunately, it seems like the school system is incredibly resistant to change. You might even say it has changed less than almost any other government institution since it was created. Do you agree, and why do you think that might be the case?

Max Planck famously said “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it,” which is often paraphrased as “Science advances one funeral at a time.”

The public school sector is…a culture which is ingrown and inbred.

The public school sector is…a culture which is ingrown and inbred.

The school system, by comparison, is nearly immortal because of two dynamics. Teachers become principals become superintendents become professors who are teachers. The public school sector is what Louis Gerstner discovered when he took over IBM, a culture which is ingrown and inbred.

The second dynamic is that education managers don’t trust outsiders, especially business people, about matters of education. Here I am sympathetic. Too many business types insist on merit pay for teachers. Merit pay, which was first tried in 1710, has been proven ineffective many times since. That kind of craziness is why many in education management so rightly distrust leaders in business, who continue to this day, to push this bankrupt idea of merit pay.

But there are methods of modern management which have been developed, such as Deming’s methods, the motivational conditions described above, and another recent development, Business Process Re-engineering, which is great for reducing bottlenecks in a school system.

But there are methods of modern management which have been developed, such as Deming’s methods, the motivational conditions described above, and another recent development, Business Process Re-engineering, which is great for reducing bottlenecks in a school system.

But the biggest problem is the dominant paradigm, that “ultimately, the quality of education is dependent upon the teacher.” The public school sector is the only sector in the American economy which blames the lowest level, teachers, for results rightly owned by system management. This paradigm is held solidly by education managers, business managers, and many in the public at large.

There is a joke about a man looking under a lamppost for some coins dropped in nearby bushes. When asked why he is looking under the lamppost instead of the bushes, he happily replies “It’s light over here!” The school system is in the bushes. And as long as we are looking to blame teachers under the lamppost, we’ll never get to the broken heart of the system itself…over in the bushes.

It is unfortunate that so many “experts” still seem to believe that reward and punishment will make a difference, as we’ve already discussed. It’s also disappointing that people still blame teachers and claim that they are the problem. There’s no question that most school teachers know more about the subjects they are teaching than the majority of adults. It’s not a knowledge problem.

Precisely. It’s a knowledge-work management problem, presently being “managed” with production management methods.

With all of this in mind, what can we do to improve the schooling system? Are there historical lessons we can point to, or should we be looking outside the school system for answers?

Migrating to a system which works for knowledge work is breathtakingly easy. There are methods of modern management which work perfectly well for knowledge work, and work immediately to get students ready, and to release the natural drive to learn.

Yes, there are historical lessons we can point to about getting school system change. Remember the change begun in 1913? Two conditions caused the entire K12 sector to adopt the 1890s Scientific Management in use till today: first, overwhelming proof of a better system (alas, in production sectors using methods which would prove to be ineffective in knowledge work), and second, directed public pressure.

The key then is…overwhelming proof of a better system, and for that, someone…must try modern methods.

The key then is…overwhelming proof of a better system, and for that, someone…must try modern methods.

In 1913, like today, there was a lot of public pressure to fix the school system. Unlike today, there was overwhelming proof of a better system which gave direction to public pressure. The end result was that education management turned like a sail, with the winds of public pressure, to adopt the system we have today.

The key then is proof, overwhelming proof of a better system, and for that, someone, in this mother-of-all-resistant-sectors must try modern methods.

So I guess that leaves us with just one more question. How do you propose to get proof of these better methods?

In four counties superintendents and school board members refused to consider trying these modern methods. In a fifth county however, which had provided professional autonomy to principals, ten written agreements were secured.

The money to fund these pilots went away when it took too long to find schools willing to try modern methods of management, so we have to re-raise the funding for these pilots. Now that we have agreements with very willing principals however, we expect to raise the small amount of money necessary to get the overwhelming proof required of the efficacy of these methods. I can already feel a breeze, refreshing, the winds of change.

i Wilms & Chapleau, The Illusion of Paying Teachers for Performance, Education Week, April 5, 1999

ii Donald G. Gratz; Lessons from Denver: The Pay for Performance Pilot, Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 86, 2005

iii Richard Murnane, David K. Cohen, Harvard Educational Review, Merit Pay and the Evaluation Problem: Why Most Merit Pay Plans Fail and a Few Survive., V56 n1, p1-17, 1986

iv Donald G. Gratz; Lessons from Denver: The Pay for Performance Pilot, Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 86, 2005

v Debra Viadero, Education Week, Texas Merit-Pay Pilot Failed to Boost Student Scores, Study Says, 11/4/2009

vi Lewis C. Solmon, Michael Podgursky, The Pros and Cons of Performance-Based Compensation, Milken Family Foundation, 2005

vii Jenny Celander, Merit Pay on drawing board for CPS, Catalyst Chicago: Independent Reporting on school reform, December 2006

viii Stephen Sawchuk, Education Week, Performance-Pay Model Shows No Achievement Edge, 6/1/2010

David DiSalvo: Why You Shouldn’t Do What Your Brain Wants You to