The self-help industry churns out Cracker Jack box advice at a startling pace, rarely with little more than anecdotal evidence to back up its claims. While some of these books offer useful advice, their lack of reference to research makes some of them counterproductive, and possibly even dangerous.

This is why I was so happy to get the chance to speak with David DiSalvo, a neuroscience enthusiast who regularly contributes to PsychologyToday.com and Forbes.com. Not content with that, he pushed forward and wrote a book: What Makes Your Brain Happy and Why You Should Do the Opposite.

Our discussion explored the differences between the world our brains evolved to deal with, and the world we live in today. What we discovered is that, sometimes, the best thing you can do is fight your brain’s natural urges.

The Interview

I’m really glad I got the chance to talk to you, David.

Thanks, I’m happy to chat.

I feel the same.

I’ll go ahead and kick this off by asking you about the title of your book: What Makes Your Brain Happy and Why You Should Do the Opposite. The title immediately caught my eye because most “self-help” books tell you what you need to do in order to be happy, and they don’t traditionally reference the science of the brain at all. So why should we do the opposite of what our brain “wants” us to do?

The question I explore in the book is whether we can rely on the native predilections of our brains in all cases. My argument—and I think the argument collectively made by the last 20 or so years of cognitive science—is that if we do, we’re going to end up doing a lot of things not in our best interests.

The question I explore in the book is whether we can rely on the native predilections of our brains in all cases. My argument—and I think the argument collectively made by the last 20 or so years of cognitive science—is that if we do, we’re going to end up doing a lot of things not in our best interests.

The underlying reason is that our brains evolved for survival, and what constitutes threats to our survival has changed in the last several thousand years. Our ancestors lived under conditions with clear threats (man-eating cats, for instance). But modern societies are significantly more complex, and while some threats are evident, others are ambiguous. Our brains evolved to predict what’s coming next and identify patterns to give us a better chance of survival. With so many ambiguous “threats” (which I define as anything that seems to jeopardize homeostasis), those prediction and pattern-detection tendencies are operating in murky water.

What this all means is that we have to pay attention to the native tendencies of our brains and work through whether or not they’re beneficial in any given case. Maybe they are, or maybe they are not. The hard work we’re faced with is making that determination.

Right. A brain that evolved for social interaction in groups of fewer than 150 people isn’t necessarily equipped to deal with the complexities of a society consisting of billions of people. It makes sense to think that doing “what comes naturally” won’t always be in our best interests.

Yes, but it’s not even the “billions” of people that really matters, but rather the density of social dynamics in just our small corners of the world. If you take just one aspect of this, let’s say the logistics of living in a mid-sized city, you’ll come up with a multi-paged list of things we have to constantly juggle, including everything it takes to maintain a living space, drive to and from work, balancing work with personal life, meeting the standards of government agencies (taxes, etc), and on and on. The level of complexity and ambiguity our brains face in modern societies is nothing short of daunting.

Yes, but it’s not even the “billions” of people that really matters, but rather the density of social dynamics in just our small corners of the world. If you take just one aspect of this, let’s say the logistics of living in a mid-sized city, you’ll come up with a multi-paged list of things we have to constantly juggle, including everything it takes to maintain a living space, drive to and from work, balancing work with personal life, meeting the standards of government agencies (taxes, etc), and on and on. The level of complexity and ambiguity our brains face in modern societies is nothing short of daunting.

It really is. In some ways it’s surprising to me that a brain adapted for survival on the African plains is even capable of dealing with such a wildly different environment.

So let’s talk a little about cognitive biases, and how they fool us into thinking we know more than we really do. We also seem to be drawn toward novel information, whether or not it is true. Are these urges that we can fight? Considering that evolution provided us with these biases in the first place, is it even in our best interest to fight these urges?

Cognitive bias is one category of brain foibles, and the list of biases gets longer all the time. I think knowing the biases we’re cerebrally strapped with can help us think and act in ways more in line with our best interests. For example, in the book I talk about “restraint bias,” which is the tendency to believe we can expose ourselves to more temptation than we really can. It’s a killer for diets, not to mention smoking cessation programs and anything else that requires pulling ourselves away from compulsive behavior. Very few of us haven’t tripped on restraint bias, usually more than once.

Cognitive bias is one category of brain foibles, and the list of biases gets longer all the time. I think knowing the biases we’re cerebrally strapped with can help us think and act in ways more in line with our best interests. For example, in the book I talk about “restraint bias,” which is the tendency to believe we can expose ourselves to more temptation than we really can. It’s a killer for diets, not to mention smoking cessation programs and anything else that requires pulling ourselves away from compulsive behavior. Very few of us haven’t tripped on restraint bias, usually more than once.

Our tendency to focus on the most available information is called “availability bias,” and it’s the reason why most people think the crime rate is far higher than it actually is. Since crime is salacious news, it’s what we see every time we tune into the news on TV. The effect is that our attention is captivated by crime to the exclusion of many other things that are more prevalent.

I wouldn’t say evolution provided cognitive bias, but rather that cognitive bias is the result of mismatches between our brain’s native leanings and our social and cultural environments.

In that case, would you say that restraint bias is the result of living in a society that is more habitual and has more excesses than the society it is pre-adapted for?

Accessibility to more of everything is a big factor. There’s very little standing between us and an ocean of temptations—many of which will not benefit us in the short or long term.

Yes. And it’s interesting to realize that knowing this on a logical level doesn’t necessarily give us the control to resist those temptations.

You also talk about what is commonly referred to as autopilot. So what exactly is “autopilot?” Why do we get stuck in this half-conscious state of mind, and what are the dangers associated with it?

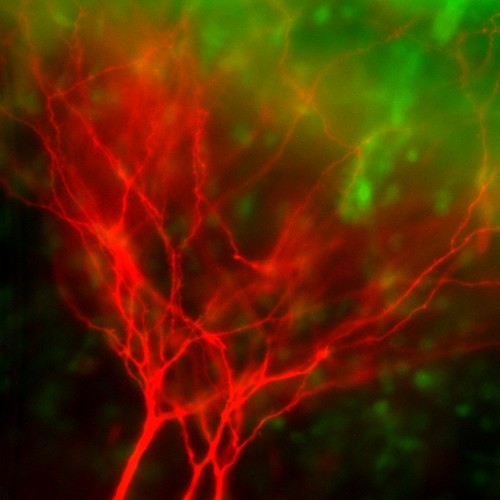

In the last decade, cognitive science has uncovered something called the “default network,” which is a neural network in our brains triggered under various conditions, with the result being that we go on what’s popularly called “autopilot.” The latest research indicates we’re in default between 30 and 50% of the time.

In the last decade, cognitive science has uncovered something called the “default network,” which is a neural network in our brains triggered under various conditions, with the result being that we go on what’s popularly called “autopilot.” The latest research indicates we’re in default between 30 and 50% of the time.

The news about this is both good and bad. Some research has found convincing correlations between default drifting and heightened creativity. We can actually solve problems in default. This speaks to our brains’ relentless processing ability and to the fact that conscious thought is only one dimension of what our brain does.

The bad news is that other research suggests the default network is triggered by boredom and stress. If we spend too much time ruminating on negative thoughts in default we’re not going to enjoy the outcome, which may include depression and worse.

It’s interesting to me that we are actually solving problems while we’re in autopilot. Does this default network exist to solve different problems than the rest of the brain, or does it just take over when the brain needs to “rest?”

I don’t think we have an answer to that question yet, though there is much conjecture about why the default network exists. One theory is that, without it, we’d lack a sense of self because our thoughts would always be externalized. Outward consciousness may be balanced by the backdrop the default network provides, and somewhere in this shifting balance we’re in touch with the “me” part of consciousness.

That theory makes a lot of sense to me. I found it interesting to learn that people who suffer from autism tend to have low activation of the default network, and schizophrenics tend to have high activation.

If the purpose of the default network is to define the internal self, much of the rest of the brain is devoted to understanding everybody else. There are some schools of thought which believe that the evolution of the human brain was driven primarily by the increasing complexity of the social group.

Whether or not this is true, it’s clear that the human being is a social animal, nothing like the solitary rationalists envisioned by enlightenment thinkers. How does this affect our thinking about ourselves and what it means to be human?

One of the scientific shifts that has changed the way we think about ourselves is that, in many ways, we’re not very different from other animal species. We are not “set apart” as both sectarian and secular traditions over the centuries have claimed. When we observe monkeys, for example, we see a slew of social behaviors not at all different than our own. Primatologists I’ve spoken to, like Frans de Waal and Laurie Santos, tell stories about their primate and monkey subjects that sound like human soap operas, including everything from affairs to jealousy to unbridled romance. Monkeys also negotiate with each other, take revenge, and wage war. Sound familiar?

One of the scientific shifts that has changed the way we think about ourselves is that, in many ways, we’re not very different from other animal species. We are not “set apart” as both sectarian and secular traditions over the centuries have claimed. When we observe monkeys, for example, we see a slew of social behaviors not at all different than our own. Primatologists I’ve spoken to, like Frans de Waal and Laurie Santos, tell stories about their primate and monkey subjects that sound like human soap operas, including everything from affairs to jealousy to unbridled romance. Monkeys also negotiate with each other, take revenge, and wage war. Sound familiar?

What I think this tells us is that being human means being part of the natural world, not distinct from it. We are a socially interdependent species just like many other examples in nature, and we can learn a lot about ourselves by studying those examples, while still acknowledging the differences.

This is a good point. I recently wrote about this while summarizing Robert Sapolsky’s lectures. All kinds of things that we used to think were unique to humans turned out not to be.

I’m a big fan of Robert Sapolsky. A truly brilliant guy.

Agreed.

So one of the things that is most interesting to me about the brain is memory. How does memory play into all of this? Why is memory so plastic? Do you think this is just a limitation of the brain’s capabilities, or is the fluid nature of memory an adaptation?

Memory is one of cognitive science’s favorite subjects, so we’re learning more about it all the time. One of the most significant discoveries is that memory is not a seamless recollection, but rather a fragmented reconstruction that occurs across multiple regions of the brain.

The adaptive attributes of memory include, ironically, that it isn’t perfect.

The adaptive attributes of memory include, ironically, that it isn’t perfect.

The adaptive attributes of memory include, ironically, that it isn’t perfect. Perfect memory—that is, the ability to recall every experience—wouldn’t serve us well for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that we would find focusing on the most important information hard to do.

There are very rare occurrences of near-perfect memory in humans and what seems clear is that those people would much rather be able to forget at least a portion of what they can’t help but recall.

I had my suspicions that this imperfection was actually adaptive. I’m sure the fact that we only remember the most relevant information keeps us from getting distracted.

…we are not computers, nor do our brains store information the way a computer does.

…we are not computers, nor do our brains store information the way a computer does.

What we call “imperfections” are frequently adaptive, but when viewed through the lens of societal and cultural bias they take on different meanings. Something like “perfect memory” seems to have great value in a world where computers can store virtually limitless information, easily accessible to almost anyone. But we are not computers, nor do our brains store information the way a computer does. This is one reason why we have to be careful about the analogies we use when discussing the brain.

Great point.

Okay. Now that we understand some basic neuroscience, what are the applications? How do we translate this information into positive action?

My argument in the book is that knowing how your brain stumbles is intriguing, but not necessarily useful — unless, that is, we can turn awareness into action. My hope is that my book conveys usable knowledge, what I call “science help” instead of “self help.” Research doesn’t give us a foolproof roadmap for action, but it does offer knowledge-based clues for overcoming stubborn tendencies of the human brain. With a little extra thought, we can use those clues to give ourselves an edge and hopefully live more fulfilled lives.

Cliff Pickover on the Beauty of Our Universe